The life cycle of an eating disorder is simple on paper. You don’t have one, then you do, and then, if lucky, you won’t again. A tidy summation, but real life is rarely tidy. The acquiring, living with, and recovering from an eating disorder looks more like an impressionist painting than a number line.

Unless you’re a TV movie or Netflix special.

I remember the day my eating disorder became full-fledged. I was eleven, sitting in the school field with a couple of friends. A quick exchange, a feeling of hurt, and then, there it was. I felt like garbage because I’d been rejected – I was the second best friend instead of the first – and I’d been rejected because I was fat. My thighs especially were out of control. They weren’t thin like my mothers.

My thighs have been a target of my hatred my whole life. You might think an eating disorder lives in the brain, but mine lived in my legs.

The violent hatred is puzzling when one looks at photos of a fully normal and averagely-sized child.

My rather active and wholly secret eating disorder continued until I tried to kill myself at age nineteen. My secret got out after that. I didn’t get better following that first attempt though I tried. I had my first inpatient stay – six weeks – and they also tried. But no one knew what they were doing so they mostly left me alone.

I lost weight.

I’ve had other inpatient stays and other specialized treatments and they tried too. An eating disorder is a hard thing to beat. It’s like chickweed – very persistent.

I just learned you can eat chickweed – who knew (aside from the people who aren’t me)?

Following on the heels of that concentrated attention in my twenties, I had years of it mostly being a secret. That is, people knew I had an eating disorder, but it was don’t ask, don’t tell. This is true of most mental illnesses. People say they want to know when you’re struggling, but experience tells me that most people only think they mean it. They want you to be better, but that’s different.

They find the details difficult. It doesn’t seem to occur to them that living with those details also sucks.

But, I digress.

And then it was 2014, and it had been thirty-five years, and I was tired, so I tried to unalive myself again. That was followed by an intervention and what I hope was my very last stay in treatment. There’s some cause for optimism – I’ve been in recovery since I left. Three months at Cedars told the tale. That, and the recognition that it was do-or-die time.

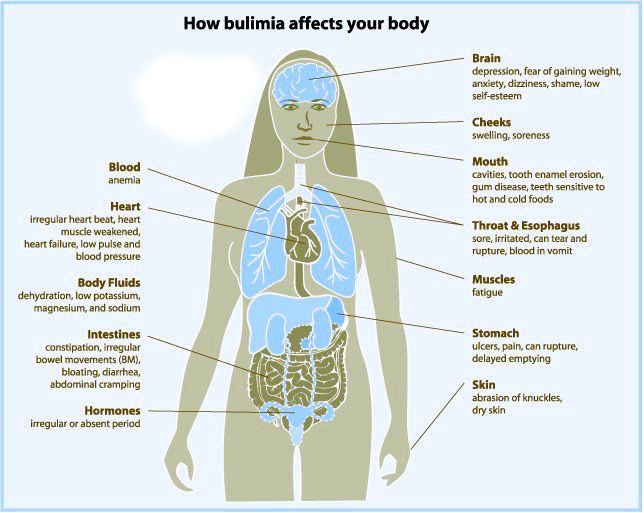

Recovery for me initially meant no purging. That’s not recovery, it’s abstinence, but it was also a miracle. I’ve purged a lot. I’ve vomited about two-hundred and fifty-thousand times. Multiple times a day, almost every day, for decades. And it’s not nice like that time you had the stomach flu. There’s much physical damage. There’s also a mental cost that’s absent when the vomiting comes from a nice case of salmonella.

Trust me on that one.

I didn’t stop entirely once I had my freedom, not at first. I stopped during the three months of treatment, however, save once, and being able to abstain showed me it was possible.

Once I was back in the real world, I purged almost immediately. Day three, I think. I also crashed. Coming out of care is an adjustment. You’d be surprised at how quickly a person gets institutionalized.

But after I purged, I went back to abstinence, and that was new. At first, it was a couple of weeks at a time. I bought myself a purse the first time I made three months on my own. And now I’m three years in and counting. Four years on Halloween.

That’s not to say that my brain came back online with the cessation of purging. I flipped into restricting almost right away. But changes had started with my thinking as well. I was rewriting my brain.

It’s taking longer than I thought it would. Recovery from something that lasted nearly four decades doesn’t happen in even a year or two, much to my dismay, especially considering the other psychopathologies.

“Psychopathology” is a fun word. Say it out loud. It rolls around my mouth with enthusiasm, much like it rattles around in my brain.

I feel a shift, however, when it comes to the real estate the eating-disordered thinking is taking up in my brain. As in, it’s less. Her voice is quieter these days, and far less insistent.

For instance: I’ve been overeating. As a result, I’ve gained a bit of weight. I’m still thin mostly thin, I’m just soft and a bit gooey. This is because I’ve been eating a lot of things I historically haven’t. Ice cream cones. Apple fritters. Chips. And I’ve been eating them as they’re supposed to be eaten, as extras. Historically, if I ate any of those at all, it would be modified (child-sized cone, for instance), and it would replace a meal.

I’m uncomfortable with the extra ten pounds. It’s settled where it always does with me, on my hips and thighs. It’s a healthy way to gain weight but I’ve always hated it. It’s typical of my body type – curvy – and I’ve always hated that too.

But I digress.

Up until quite recently, I was still afraid to eat a lot of things. I avoided reintroducing a lot of banned foods. I remained worried about accepting a different body. And what if I got fat and bad things happened? But bad things happen regardless of weight. I knew that, but I didn’t know it if you know what I mean.

Things have changed for me fundamentally and there’s a weirdness to that. I’m not sure what happened or when. It’s probably the cumulation of several things. I do know the shift is relatively recent.

I think I’m in my “fuck it” era.

(to be continued)

Congrats on nearly four years—that’s a massive achievement!!

I’ve not had to battle an eating disorder, but I have certainly spent the majority of my life hating parts of my body—I don’t think that piece of it is uncommon at all.

I know NOTHING about chickweed. Would you WANT to eat it?!

I think most people want to fix problems, and want to support those they love through problems. The difference with mental illness is that there sometimes is no fix, or the fix is years in the making. People tend to give a lot of energy towards fixing (or supporting a loved one through) a problem at the beginning, which is great, but that support is really needed throughout. Folks tend to turn away from hard things—or at least move it to the bottom of their to-do list when everything else in life is vying for their attention and support.

“It rolls around my mouth with enthusiasm”—I LOVE that description!!

Celebrate being in your “fuck it” era—I hope it sticks around for a good long time!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you.

Yes, that’s what makes me sad about approaching a kind of normal – it’s still about disapproving of the self 🙄

Chickweed is this hideous weed that’s wicked fast at reproducing. If you don’t get it before it grows the stalk, as soon as you touch it, it shoots off a huge handful of seeds in all directions. It’s evil but, if things get dire, it’s nice to know I have food options. 😂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup, we’re all self-critics.

Ick. I’ll bet it’s bitter AF.

LikeLiked by 1 person

😂😂😂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done for all the progress you’ve made. That’s a massive achievement and worth celebrating. I wish the life cycle of an eating disorder was more straightforward, I’m battling relapse at the moment. But knowing you’ve been able to change things after all this time is an encouragement to me. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you reading and commenting. I’m sorry about the relapse. We’re so hard on ourselves when we do, we instantly discount everything that wasn’t a relapse.

I’m with you on the shape of recovery. A straight line, or even stairs. This up and down, back and forth is frustrating.

LikeLike